The Life of the Nameless One

- ruogu-ling

- Oct 8, 2025

- 10 min read

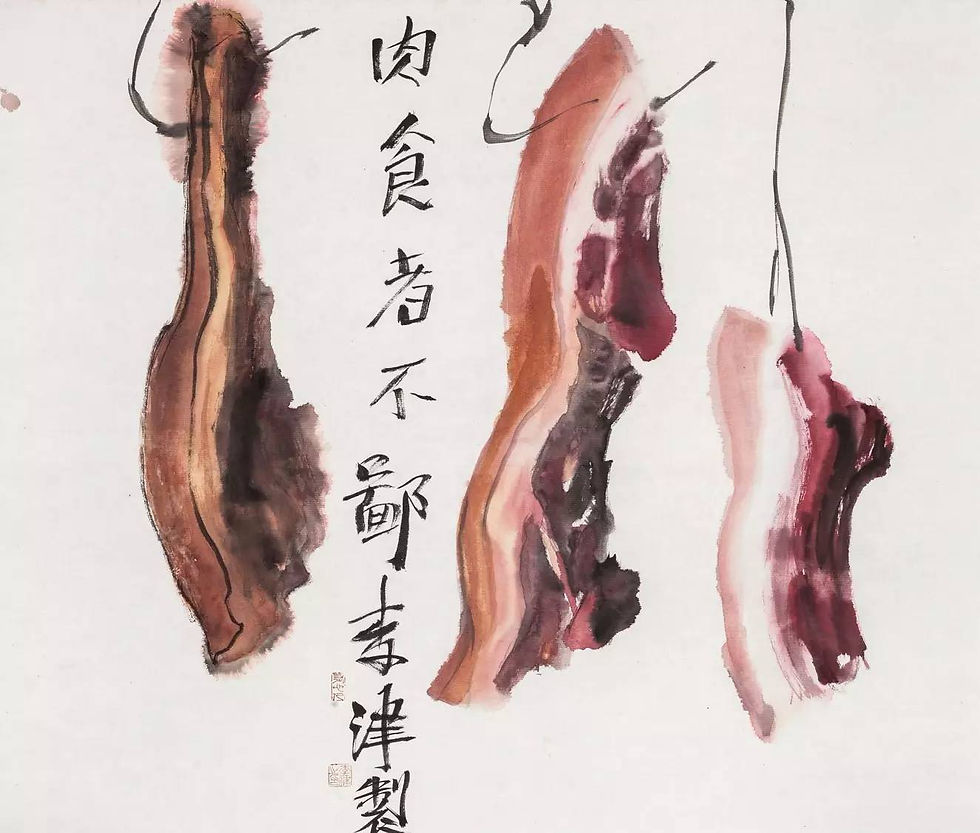

Li Jin

I want to begin by explaining why I came up here carrying this basket.

I’ve been carrying it for about thirty years now.

Back when I had just stayed on at the Academy of Fine Arts as a teacher, I used to ride my bicycle to class with this basket, because I would pass a market on my way home and needed to buy groceries.

This basket has been with me ever since.

Later, apart from school, home, or the market, it went abroad with me; it went to concerts and exhibitions; it even accompanied me when I received awards.

It’s been on stage with me for prize ceremonies.

Over time it became something like my logo.

If someone says, “There’s a man named Li Jin—what does he look like?” people will say, “He’s the one with a beard and a basket.”

If there’s only a beard and no basket, that might not be me.

So I brought it again today; I can’t wrong it by leaving it behind—it should keep me company.

Why start with this basket?

Because this little logo of mine actually isn’t far from life itself, and it’s close to the focus of my art.

In my generation, parents didn’t deliberately cultivate their children in anything.

Both my parents were very busy.

When I was little, I was hyperactive and mischievous; they couldn’t control me.

But they found that when I had a piece of paper and a pen, I could draw for hours—so they thought maybe this child had some fate with painting.

Later, when I thought back on it, I realized that I was such a restless child—I couldn’t read; after two pages I’d fall asleep, not a studious type at all—but drawing always fascinated me.

And I think it’s because when I started drawing, I was inventing stories for myself on the page; I was absorbed.

When I picked up a brush, I believed that the pictures on the paper were real.

It was a way of amusing myself—tricking myself happily.

Now, at my current age, I realize that I’ve been entertaining myself like this for fifty years, and that original motive, that interest, has never changed.

When you draw, you can forget everything around you—your social roles, your life roles, the roles people assign you.

All of them disappear.

Facing a picture, you only think about the image itself—your true world—where you can drop everything and converse with the paper, the colors, and the brush.

I remember when I was young, everyone promoted war themes—always drawing the Eighth Route Army fighting the Japanese.

I’d imagine them surrounded on a mountain, the enemy about to take the peak—

then I’d draw two more machine guns to suppress them.

That feeling—wanting so badly to have firepower to help—

and all I had to do was draw two guns.

In life, of course, that’s impossible.

Maybe what you hope for in life is never so easy to achieve,

but in a drawing, you can freely place your desires and satisfy yourself.

I entered the Academy of Fine Arts in 1979.

This photo was taken in my first year.

My outfit then was standard—very proper, very much like an Academy student.

And this painting was also from that first year—

a rural child from the Taihang Mountains in Hebei.

This kind of work was very typical then:

it had to be simple, realistic, and truthful.

That was the essence of orthodox fine-arts education at the time.

We admired our teachers, most of whom followed the realist path—academic skill, a sense of reality.

By the time I reached the upper grades, reform and opening-up had begun—the 1980s.

Our art education began to receive Western influence.

We wanted to open our minds, to pay attention to Western trends.

We actually knew Western art history better than Chinese art history then.

My idols changed.

I admired Van Gogh and Gauguin.

They seemed pure, intense, willing to sacrifice for art;

their lives were tragic.

At that time, I was young and earnest—longing for depth.

Not pretending to be deep—truly longing for it.

Under that influence, I began to change.

The change was huge.

Strictly speaking, I had never lived in society:

from elementary school to middle school I studied crafts,

then went to the Academy,

then stayed on as a teacher.

After I was assigned to teach, the school happened to have a chance to send faculty to Tibet—

many universities in Tibet then depended on mainland teachers.

Originally I wasn’t chosen,

but I cherished that opportunity.

The teacher who was supposed to go couldn’t,

so I fought hard to take the spot.

Why? Two reasons.

First, as I said, I loved artists like Gauguin and Van Gogh.

Van Gogh longed for the sun—you can see it in his sunflowers and the bright colors of Arles.

Gauguin went to Tahiti—to a primitive world—to seek the original bond between humans and nature, between humans and animals.

Those ideas affected me deeply.

And Tibet, I felt, combined both.

Back then Tibet wasn’t like today—few people knew it or could reach it;

transportation was poor.

So the Tibet I imagined was magical.

My transformation there was intense.

Let me show you: I trained in Chinese ink painting, using a brush,

but in Tibet I painted things totally unlike traditional ink—

different in aesthetic, subject, and spirit.

At that time it was a bold choice—a breakthrough.

The intensity didn’t come only from my imagination;

the environment itself gave me that shock.

It was natural.

Some might say Western modernism influenced me,

and I don’t deny that,

but for me, those works came from Tibet itself—

a place where people and nature, people and animals,

felt so close that humans had an animal quality,

and animals seemed human.

That was something I’d never felt at the Academy,

but in Tibet I found it—in expression and emotion.

My generation all carried a heroic complex—

a longing, a pursuit of the feeling of life.

People then were rising upward,

feeling not far from heaven or from gods.

In Tibet, I truly felt close to the sky.

So to search for ideals and illusions felt natural.

But when I came back from Tibet to ordinary life—

back to the marketplace—

that became an important transformation for me.

Because it was only after Tibet

that I realized how important daily life was.

I had gained the experience of life itself.

What do I mean by “the experience of life”?

In Tibet I went into uninhabited areas.

I won’t go into detail—there isn’t time—

but things like witnessing sky burials—

those experiences at such a young age changed my worldview.

I went from always wanting to fly

to realizing I had to land on the ground.

Because you feel how short life is,

how small each person is within the great cycle of existence.

So when I returned to ordinary life,

I became more grounded than before Tibet.

Toward life and toward friends,

I no longer felt the need for distance or separation.

I came to another extreme—

amusing myself again,

playing with life, finding joy.

Everyone, no matter how deep, has humor inside;

some hide it, some express it directly.

My paintings from that time were again cross-boundary, alternative.

In the 1990s, most people wanted “higher,” grander, more avant-garde art.

But I suddenly shifted from a radical artist back to the essence of life—

looking around me,

turning conflicts into humor,

giving things a sense of joy.

That had to do with my experiences.

I thought: always frowning isn’t good—

the result will be tragic, whoever you are.

So life should make you happy.

If people influence each other with joy,

the world will be calmer.

Whatever your role, whatever troubles you have,

you can transform them somehow.

For me, painting does that—

it’s the best outlet for my emotions.

Then came another change.

By then I was around forty.

People at forty often feel nostalgia.

And life—everything around me—was changing fast.

I felt my old memories and present life mixing,

somehow connecting.

We already had entertainment—massage, cupping, things like that.

But I felt that for people like me,

all entertainment carries something positive.

When I painted things like The Old Doctor Feeling the Pulse of a Female Soldier

or The Red Sister Saving a Soldier,

I thought: eroticism lies in the heart, not the subject.

A nude figure can be erotic or not—it depends on the viewer.

It’s not that the human body itself is indecent.

So don’t judge by form or topic.

First, ask whether what you see is a vivid person,

someone with blood and flesh.

That’s what I always pursue:

what you paint must be lifelike, must have vitality.

The subjects I touch rarely appear in traditional literati painting

or in our so-called historical masterpieces.

But I’ve never believed that Chinese painting must continue the literati or “pure beauty” traditions.

That’s not so important to me.

If I can express my real life and feelings through my brush and ink

so that others can feel them too,

that’s enough.

People worry that today’s Chinese painting is too distant from our era—

how can we use old aesthetics and techniques to face modern life?

But form doesn’t matter; you matter.

Do you observe your life?

If your life, in your heart, already has an image, then paint it.

I’ve painted computers, televisions—why not?

Even modern buildings—no problem.

These are not barriers keeping ink painting from being contemporary.

I’ll admit I speak worse than I paint.

But since I’m here, I have to speak.

No matter what I say, I suggest you look at the paintings—

because if I could express what’s in them through words,

I wouldn’t need to paint.

That would be easy—just talk, and you’d get the same pleasure.

But painting is painting.

Among our generation, few younger artists still like my kind of work,

so I’m content.

If your art can influence several generations, that’s amazing.

But I never tried to “serve” young people—

not by studying them to make my art seem young.

Inside, I simply follow the times.

Fashion and the spirit of the era project strongly onto me.

What kind of person am I?

I think I’m a good conductor.

Maybe I’m like a blank sheet of paper—

but my senses work well, I’m perceptive.

That’s crucial.

I don’t block experiences.

Some people close doors inside themselves;

I dislike that in an artist.

I hope I can always stay young, always full of life.

How to nurture yourself?

Respect your feelings, and follow the times.

What does “follow the times” mean?

As we say, brush and ink must follow the era.

Don’t oppose the life around you.

I don’t believe resistance is a choice.

Get as close to life as you can,

keep your communication with it open.

Many of my paintings show scenes like feasts, gatherings, meals.

Early works were more personal,

but after 2000, I wasn’t satisfied just painting private life.

I remembered that as students we all talked about ideals,

and mine was “to treat a hundred people to dinner.”

Back then, people thought that was crazier than achieving communism.

But I did it.

From early on, I wanted to build joy on sharing—

everyone happy together—

not secretly enjoying something alone.

This personality naturally shaped my art.

I can’t help thinking about communication with others.

So I often say:

if a painting has friendliness,

its painter can’t be closed off.

Many people like my paintings even without knowing me.

If the work makes them happy, that’s enough.

And you can be sure:

if you meet me in person,

I won’t be very different.

If I were, that would mean the work was false.

This photo shows an exhibition I did at Today Art Museum.

Because I painted The Banquet,

and in real life I often invite friends to eat, drink, sing.

So I thought: why not bring that life directly into the museum?

Museums usually don’t allow eating and drinking,

but I worked hard and made it happen.

In the first photo, we’re eating in my studio—

and then we moved the same thing into the museum.

The joy and form were exactly the same.

When I host dinners at home, I often prepare flowers and decorations—

make it feel like an artist’s party.

Inside the museum, it became an art piece.

People looked at it and thought its value had changed.

That’s what I oppose.

For me, the museum is just a wall.

Something inside a frame on display becomes “art,”

but in life, the same thing is just entertainment.

That’s wrong.

If you truly have an artistic sense,

you can respect the small moments of life as art too.

And if you only see art as what’s inside a museum,

you’ll never really participate—

you’ve already placed it on a pedestal,

and that’s not right.

After all this, I still believe:

don’t give up the details of life around you.

Don’t rank things by high or low, big or small.

If you have a garden or just one flower pot—

if you love it, they’re equal.

Maybe one pot is even better—

easier to care for, more focused.

Of course, a flourishing garden also needs your capacity

and the same devotion you give to one flower.

That’s a kind of wisdom.

Look at the paintings.

I always emphasize:

I paint what I like, what I feel.

When you see things like braised pork in my works,

you know the painter loves to eat.

That’s important.

Don’t choose wrongly—

a vegetarian shouldn’t paint pig heads; that’d be disastrous.

So the smart choice—the easiest—is your own surroundings, your own loves.

Most artists don’t die from painting—they die from overthinking.

So don’t think too much.

Treat it sincerely,

use all your intelligence and technique.

If your hand isn’t skillful, even simple things won’t express well.

This is one of my “banquet” scenes, full of food.

You can immediately tell:

the painter is no vegetarian,

and not indifferent to women.

And that’s fine.

To me, “the color and fragrance of life” means affection, enjoyment.

You might not like food or sensuality,

but you must like something.

If you live without liking anything,

then no matter what you do,

you’ll lack motivation.

This was in New York, during St. Patrick’s Day.

When I saw Beijing full of green once, I thought we were celebrating it too.

Then I asked and found out it was just soccer fans for the Guoan team—

but the green was exactly the same!

I even called my American friends, saying,

“China’s amazing—Beijingers are celebrating Irish holidays!”

But I was wrong; we weren’t that connected.

I painted this in New York.

It challenged me in two ways.

First: could I paint a green hat in America?

In China I’d never dare—no one would buy it!

Who wants to bring home a green hat?

Second: could Chinese materials,

this form of painting,

express foreign moods?

Could I capture another culture and aesthetic?

I think yes.

Now, with such fast communication,

there are no more closed corners in the world.

If you start from humanity,

from instinct,

and have the language for it,

there’s no obstacle.

Many of my collectors are African, for instance.

Carrying the weight of such an old, traditional medium,

you still can connect with contemporary life.

I’ve proved that—it’s not a problem.

Finally, this series.

One year I went to Qingcheng Mountain in Sichuan.

It was Lunar New Year’s Eve.

Why go to such a place alone for Spring Festival?

Because that year had been too lively for me.

So for the holiday I went alone to the mountains,

close to Daoism, close to nature,

to enjoy solitude.

When life is too noisy,

the joy of solitude feels different.

It was as if all the muddiness of the year was washed away.

There was no one—

even the guesthouse owners had gone home for the holiday.

I was alone in the building.

I, who’m always surrounded by feasts and laughter,

lived simply there,

and suddenly felt a quiet joy.

It was as if the clouds parted—

a sense of descending,

of seeing each grass and tree clearly,

of a pure breeze passing by.

I realized: after prosperity,

true nature appears;

in simplicity, one finds heaven’s charm.

Comments